Wednesday, January 14, 2009

Google’s Real Fight in China

By Michael Liang Zhang & Yan Luo

Michael Liang Zhang is the assistant managing editor of Global Entrepreneur magazine, where this article originally appeared in Chinese language in November 2008. Michael, whose own “20% percent project” is a blog focusing on Apple, followed Google China’s story for three years now and has interviewed many of Google China’s employees. Yan Luo is a reporter of Global Entrepreneur magazine. She covered the internet and venture capitalist scene for the magazine for three years.

It was a cold day in early 2008 when Kai-Fu Lee received an unexpected call from a key figure of Tencent Inc., who threw a question, polite but surprising, to Mr. Google China.

“Is there any chance for QQ to take over Google China?” asked the brain from the first 10 billion dollar worth Internet company in China. Both ends of the phone knew, It’d be an A-bomb dropped into the Internet crowd in China to merge Google China’s ambition into the world’s largest instant messenger user community.

However, the questioner might have overestimated the wow factor from Lee. It sounded like anything but a mind-blower on the receiving end of the call. This was not the first time Lee was asked to think about selling Google China to Tencent. Back in mid-2006, when Google China’s vitality was dimly blinking, some executives in Mountain View suggested building a joint venture with Tencent and put Google’s China operations into it. The proposal was shelved after drawing strong rejection from the management of Google China, who argued that such a move, in that very down time, would destroy the faith of both outsiders and employees in the company.

Again, Tencent’s offer ran into a dead end. But the two discussions exactly demonstrate the magnitude of possible changes a global company would face when it tries to adapt itself to the China market. In the last three years, Google China has been in spotlight, which, however, was most often cast upon the visible vulnerabilities: constant rumors of Lee’s departure, the thievery stain on Google’s Pinyin sleeve (Google’s Chinese Input Method Editor was caught plagiarizing), or just the never-ending comparison with Baidu. Never expect that these controversies are enough to jigsaw a whole picture of the Internet giant struggling in the over-competitive market in China. Real questions still remain unanswered. What are their true challenges? What can they do to avoid the worst nightmare? How has Google China managed not to fall as so many foretold? Or, at least, why can Lee stay safe, instead of being kicked out after so many rumors and fights?

Google’s China stories mean more than the hard life of a company. Powerhouses like Coca-cola and P&G, often quoted as the most successful multinationals in China, have learned a great deal from their presence in the market from the dawn of China’s open-door era. Microsoft, at the same time, has built itself an image of a mammoth entering hunters’ cave. Unlike any of the predecessors, Google now represents a new breed of global players, who sit on world-class brands, technologies and impressive talent pools while suffering the extremity of fierce competitions that even a daring U.S. company can never imagine. Before and after Google, nearly every Internet giants with a high aim in China now live a miserable life. The fate of Yahoo, eBay and MySpace put Google’s life in China under much more pressure, jeopardy and misunderstanding.

Reality Distortion Field

Google China’s Beijing office building in Tsinghua Science Park

Let’s start from the basic question. Can Google claim that it has survived its darkest time in China?

The answer is surely positive. According to the statistics from Analysys International and China IntelliConsulting, both Internet market research firms, Google now enjoys a market share of more than 25% in China, which nearly doubles the number in the first quarter of 2006 as Analysys shows.

It’s far from a win. Google still lags way behind its archrival, Baidu, in the search market in China. The latest figure shows that a 65% market share goes to Baidu. But, most important, it’s alive. Even more vigorously.

“You guys are gonna get out of the country.’” Recollects Jun Liu, head of the research arm of Google China. “In 2006, so many people said this to me.”

In contrary to the usual perception, Google has never given a peek at the exit. But truth is that it did tune down the forecast to a very low point. In 2005, when Lee was still stranded in Microsoft’s suit against his leaving, Google had already prepared a Plan B: a smaller office in China if they lost the case. And in early 2006, when Google was on the edge of closing Google.cn for the controversy over its lack of a legal license, Sergey Brin, the co-founder, told Lee that all the China office staff will be kept even if the operation here was stalled.

“If we go public ... we’ll be one of the largest NASDAQ-listed Chinese companies.”

Fortunately, Google made the survival record among the ailed global players. It sometimes could hit a good ball. In 2008, Google was more than once mentioned with some successful local offerings, like Guge Yinyue (Google Music Search, only available in Mainland China) and the acclaimed Chunyun Ditu (Google Map for Chinese Spring Festival travel season).

Revenues pick up, too. According to three different sources who know the financials of Google China, their sales numbers are much closer to Baidu than their market share gap. “If we go public,” an executive of Google China told Global Entrepreneur, “we’ll be one of the largest NASDAQ-listed Chinese companies.”

But their hard time is yet to be over.

In fact, Google hasn’t come into the real battle with Baidu. The past three years witnessed that Google and Baidu were both growing over the dead bodies of other competitors in the market. Now, with the duopoly era starting to dawn, the two titans have to engage. But their most important weapons are probably not the search technologies, but their brands. When a new user is born on the Internet, what search engine will first come into his mind?

Google China’s boss, Kai-Fu Lee

For that, Baidu got a fatter chance. Lee now has strong enough reasons to claim the lead of his team in Chinese-language search technologies. But a test shows that users will favor Baidu when the logos of the two companies are shown, even if most of them think Google provides a better result in blind tests.

“I always encourage people to leave Google China to start up new companies.” [Kai-Fu] Lee said, “And I’ll feel proud if their business plan turns out to be great.”

Lee acknowledges that Google could only score 60 in the brand awareness, even he himself would give perfect grades to its hires, technologies, products and sales.

Branding is the weakest link for the capable Googlers all over the world. Google was well known for its no-ad psychology. Google never dreads spending. Just look at the 900 million dollars Google would pay to place its query box in MySpace.

You can do the math. Word-of-mouth communications usually have an exponential effect on the market share. The meaning: nine out of ten new search engine users are recommended to use Baidu. Google might lag even further behind Baidu in the fast growing market, unless it can beat Baidu in brands. Many ex-Googlers believe that this will be the biggest challenge Google China needs to face.

To make it worse, some may think, Google has bid farewells to many veterans, including James Mi, Director of Corporate Development, Alan Guo, Chief Strategy Initiator, and Tina Tao, Kai-Fu Lee’s personal assistant. “I always encourage people to leave Google China to start up new companies.” Lee said, “And I’ll feel proud if their business plan turns out to be great.”

Lost in Translation

Yahoo’s search market share in China plunged from 21% in 2005 to 5% at the end of 2006. The sixteen percentages were plainly available for people to grab and that could have been Google. But Microsoft’s lawsuit against Lee froze Google China for half a year.

Google got a lousy start in China and it was easy, for outsiders, to blame the incompetence of its local products for its shameful market share drop in 2006. But it was easy, too, to neglect another important variable.

Just a month after Lee handed his resignation letter to Microsoft in 2005, Jack Ma, the e-commerce tycoon, pocketed Yahoo’s China business. These two incidents nearly set the tone of the Internet industry in China for the next five years.

Seen as an Internet maverick in China, Ma, a college English teacher, built his online catalog of Chinese manufacturers into a cash machine. Later, he entered the online auction business and smashed, bare handedly, eBay’s market share in China to single digit from an overwhelming 80 percent dominance. Yahoo China was just another trophy he won along his road of never-ending success. But the new boss lost his sense in search. Ma killed the joint search project with Sina.com, ignored engineers fleeing 3721.com, the real-name search pearl Yahoo China acquired, and did nothing to stop its image from the beleaguer of Zhou Hongyi’s Safeguard 360. Zhou founded 3721.com and left Yahoo China as the president.

According to iResearch, Yahoo’s search market share in China plunged from 21% in 2005 to 5% at the end of 2006. The sixteen percentages were plainly available for people to grab and that could have been Google. But Microsoft’s lawsuit against Lee froze Google China for half a year. Besides the suit, there were still many things Google needed to clear before getting a good start in China. Their China team, if there were any, hadn’t done anything for the company to fully operate locally by early 2006.

It should have been a big fight over the room Yahoo ceded. But, no, nothing big happened. Baidu took the meat without any pain and advance its market share from 37% to 53% in less than one year.

That was just the beginning of the nightmare of Google China.

The China Dilemma

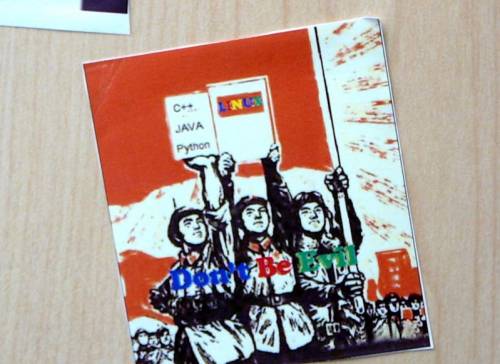

On the wall of a Google China office

It shocked Alan Guo, then the chief strategy initiator of Google China when he found in September 2005 that the search queries they got plummeted 18% in five months. Thanks to the Great Firewall, users would find Google down for several minutes after they tried to search with keywords banned by the Chinese government. If more than one users share one IP address, all would lose Google, momentarily, when one of them Googled wrong words. The statistics showed that 5%-10% users will be shut out of Google at any time.

This is a typical dilemma Google China was thrown into. Solution to the problem is easy: redirecting users to a local version of Google, which filters everything Beijing finds uncomfortable. But this would be even more challenging. Google needed to compromise its no-filtering creed and to apply for a license from Chinese.

Why, many hardcore Googlers in Mountain View asked, bother to do something so much controversial just to get in a market? Gradually, it became justified as Lee insisted that it’s just the due respect to the local laws. Word game? Maybe. But this self-justification psychology started to be part of Google China.

All multinationals’ failed attempts to get adjusted in China are either fruit of losing local touch or eradicating their global roots. There are even worse ones, who are stuck in-between. Google China looks like the last. The only difference is that it survives with a good balance. “The Golden Mean is just the result of fighting on two fronts,” says Wang Hua, Google China’s business developer. Google China even stands more still as it takes difficulty to manage the clashing cultures.

It haunted the Chinese Googlers literally everyday in February 2006 that their government relation colleagues might come back with the bad news that they needed to be closed down the next day.

Self-convincing, of course, wouldn’t guarantee Google China be free from worries and hastiness. To make itself operate legitimately, Google hurried to borrow the license from Ganji.com, a local online classified ad service provider invested by Google employees. According to sources close to the deal, Google had planned to acquire Ganji.com before the plan was rejected. It was not a wrong decision, but it did shut the gates to more possibilities.

And the license borrowing almost turned out to be a devastate. The Ministry of Information Industry of China soon started an investigation into the suspected “illegal operation” of Google China. It haunted the Chinese Googlers literally everyday in February 2006 that their government relation colleagues might come back with the bad news that they needed to be closed down the next day.

It was not until July 19, 2007, two years after Lee joined Google, when he finally made the announcement of a granted license. For the first company to put “don’t be evil” in its IPO filing, to comply with the regulations and laws of a totalitarian country looked just so inconsistent. Its Chinese filings, thus, needed to be worded carefully to get through the long process of cross-department review in Mountain View before sent to the Chinese regulators. When anything was modified, which happened every time, the whole process had to be run again.

Its rivals wouldn’t stop, at the same time, trying to strangle the Chinese newborn of the search giant. It was told that from 2005 to 2007, piles of reports on Google’s “anti-China” search results would be presented to the Chinese regulators nearly every two weeks.

“The reason why we eventually got the license was that our rivals couldn’t find anything more against us,” a Google China executive told Global Entrepreneur late 2007.

Stay in business

It’s an endless war, people tend to think, between Google and Baidu, and their battles could seemingly escalate at any time. But the truth is that there’s not an all-time engagement of the two companies, despite their intensive watch over each other.

“After Baidu grabbed all the share of Yahoo China, we realized that the only way to fight Baidu is to stay in the business”

Actually, in late 2006, many Internet heavyweights started to show their feeling of disappointment with Lee & Co., who were thought to be in lack of aggression and boldness. Baidu even began to find itself a new archrival, at least a short-term one – Alibaba.

“I don’t think they’d go any further,” Robin Li told Global Entrepreneur magazine, at the end of 2007, when asked whether he would worry about the likely threat Tencent posed against his newly born instant messenger, Baidu Hi. “Just look at Soso.com, their search engine.”

Google didn’t turn its head away. “After Baidu grabbed all the share of Yahoo China, we realized that the only way to fight Baidu is to stay in the business,” Alan Guo says. “There’s no silver bullet that kills Baidu. You can only wait till they slip first.”

The conservatism in Lee’s carefully devised strategy was the result of his conclusion that there was no way for Baidu to totally knock Google out, which was in its best time and had all the resources to support a lengthy regional war.

For a game plan like this, the least affordable is any change to the strategy. Lee, not as much a search expert as a sophisticated manager, knew how to make a team stick to something of such an importance – cut down the goals to the very core and keep coming at it. Lee came to the realization, probably earlier than anyone else, that the continuous improvement of search quality is better than trying one hundred means to boost traffic.

The decision wasn’t agreed upon by many people, even including Lee’s then partners, Johnny Zhou and Alan Wang. It turned out to be a smart move, however. Although looking dull and not helpful in drawing people’s eyeballs, it is the cornerstone of Google’s competency, with measurable results and without Lee reinventing the wheel.

“I’d have been dead if I had been asked to start to try social network services,” Lee once joked to us.

Baidu ... had never felt the real pressure from Google until the end of 2008, when Baidu found that the workload of its manual “optimization” of irrelevant search results was exploding.

The conservatism also helped Google China, haunted by so many headaches, to concentrate on clearing each one at a time. Launching Google.cn stabilized the access to its services. The Suggested Searches and Guge Pinyin threw its inaccuracy in Chinese keywords analysis into the past. The Chunyun Ditu shifted its image of a suspected plagiarist. The One Box feature – like the instant results Google delivered when you searched for “gold medal” during the 2008 Olympics – silenced the criticism on its slowness in crawling pages. People even laughed at its official Chinese name (Guge, which translates to the not-too geeky “Song of Harvest”), citing the difficulty in pronouncing and writing it, and now they got a g.cn. And its acquisition of small local companies and preparation for the Internet Café market indicate Google’s ambition for low end users.

According to three different sources close to Baidu, the Chinese company had never felt the real pressure from Google until the end of 2008, when Baidu found that the workload of its manual “optimization” of irrelevant search results was exploding.

Apart from improved quality of its products, Google’s gain in market share was also the result of the search boxes in more and more associated sites. The partnership between Google and Sina in June 2007 marked a milestone for Google. Its market share didn’t explode out of the deal right away, but the Chinese users and advertisers value it greatly. While Baidu is weak in building partnerships like this, Google continued to ink deals with carriers like China Mobile and China Netcom, Internet portals like Sina and Tencent, and vertical sites like movie fan or style.

Google is strategically conservative, but definitely not ignorant. Google even learned, sometimes, from Baidu. The idea behind Tianya Wenda (Tianya Q&A), its co-operation with the largest Chinese forum, is pretty much the one that draws users from Google to Baidu. Tianya Wenda won’t necessarily catch up with its Baidu counterpart soon, but at least Google now has something to leverage against Baidu’s monopoly in the Online Q&A service and its attempts to block Google’s site crawlers.

Everything communicative

Many times, the archrival of Google China is not Baidu, but Moutain View.

Charles Zhang, founder and the chief executive of Sohu, always likes to say that the killer of Yahoo China is the nature of multinationals, which brings long decision chain and lacks in really local prospective. None of the global Internet companies can excel, Zhang insists.

Empowerment is never the problem for Kai-Fu Lee. But Google’s persistence and sensitivity in its moral principles and integrity sometimes are bigger barriers. Its huge success fortifies its extreme confidence in its way of doing things. Branding, for instance, is the last thing for Google to consider in the United States while it’s taking pains to penetrate into a vast, ill-informed market like China.

Some would point at the too many limits it is put under. Say, it’s not a start-up any longer and it’s not a local Chinese firm. Google has to please too many different, or sometimes even conflicting, interest groups. Chinese law versus Google’s morals. Privacy of user information versus governmental control. Chinese culture versus American style. And the Chinese engineers can nearly do nothing without thinking about either the Chinese political correctness or their Mountain View cubicles maps. All these mean that the appraisal system would be a challenge, too, if Lee can’t get them motivated to feel free to bring on things as innovative as Gmail and Google Earth. Flying across the Pacific to get things done may be more intimidating than leaving for a start-up.

Lee succeeded in dragging people out of Mountain View and throwing them into the wild world of Chinese Internet Bars.

Internal communications, thus, becomes one of the essential work Lee has to do well. Lee grew up and was educated in the United States, and worked later with industry heavyweights like Bill Gates for years. Many Googlers agree to us that Lee’s experience make him the perfect bridge between Beijing and Mountain View.

“Kai-Fu is very good at pushing things forward,” says Alan Guo, who has worked with Lee for many years. “One of the best things about him is that he can see your merits and find out a way for your to co-work well.”

Many Chinese engineers just can’t figure out how Lee can handle hundreds of e-mail messages everyday, sorting out things, matching perfect personnel with them and allocating resources for them. He knows how to persist in some key things, like the launch of a local domain under Chinese laws and relocation of servers to China.

Lee later acknowledged that moving servers will add up big costs. Data centers are the physical hearts and minds of Google. Each one of them is so vast that only a few countries and regions around the world can host them. “China is super important and everybody knows that. But the huge amount of modifications to the software and hardware, the extra customs tariff? Is it worth all of these? Will we have much different results out of it? We need a good debate on that.” Lee says.

At least, Lee succeeded in dragging people out of Mountain View and throwing them into the wild world of Chinese Internet Bars.

Back to the days before Google set up its first office in China, many Googler were sent from the U.S. to observe the Internet Bars in China. Seeing youngsters use computers just for music and gaming, they figured that the bars have nothing to do with search, Google’s core business, until they realized that Internet Bars are often the first place for young Chinese to access Internet. When announcing its Chinese moniker in April 2006, Google China arranged a group tour for the Mountain View executives to Internet Bars, many of whom still find it difficult to understand the unique form of Internet life. Lee just needs more solid data and strong experimental result.

In 2007, Google started its pilot project for Internet Bars. Wang Hua, head of the project, knew what Mountain Views needed, for he just worked there in a few months. “Throw yourself out on the street, find your target users, do some tests, get your clues, and build your test into a formidable case with cross-department collaboration,” Wang explains. “Never try to start big. Never try to change their minds in the first place. Prove your idea with small successes.”

Some of the questions Wang needed to answer are just figure questions. How will users be impressed in high traffic places like the Internet Bars? Will the positive influence remain even after Google stops the collaboration?

The stat meter Wang placed in Internet Bars indicated an increase in the usage of Google’s products, which proved the positive influence. Statistics also showed that areas near schools are not as high-traffic as expected and that a certain collaborative products would be spread out of the bars in the area.

Other questions were not really questions. They were just miscommunications. Mountain View expressed their worry when they learned that Wang’s team made Google the default homepage on the computers browsers in the partnering Internet Bars. Will that compromise users’ right of choice? “You have to explain to them in the most plain language,” says Wang. Users don’t have the ownership of the computers in Internet Bars, Wang explained, and, technically, they are more like renting it from the owner of the Bars. So, users just don’t have the right to install tweak something in the machines.

With two years past, Wang is the new star in Google China. He knows the local market as well as the psychology in Mountain View. He pushes things hard and fast, the reason of which, Wang likes to say, is to “stay firm.” “Many of my projects last long, like two or more seasons. But I never try to look for any conflict or bias. When I do something, I just keep emailing the related leaders.”

Creating values

Finally, Google needs to talk about its brand and accept it as an indirect but necessary way of penetrating into the markets.

Google starts to work with other companies on co-branded products. Google Kingsoft Ciba is one example. And it’s more than a marketing campaign. When Google isn’t idling away the time while waiting for a star product to get born out of its own lab, it can now think about paying money to put its logo on some of the good but unfortunately unprofitable products.

Alan Guo was the brain behind the deal. After some discussion with Lei Jun, Kingsoft’s ex-CEO, the first idea was just to embed a Google toolbar in Kingsoft’s products.

As Guo got into more details with Lei, who Guo came to know when he helped Amazon.com acquire Kingsoft’s Joyo.com, he found two interesting things happening. One is that Google China’s translation was seeing a drastic increase in traffic, which demonstrated Chinese people’s eagerness to learn English. The other is that still very few Chinese consumers are willing to buy legal software products. Kingsoft Ciba tops the translation utility market but makes no money out of the pirated circulations.

These findings led to a conclusion that Google’s advertising-backed model can support Kingsoft Ciba financially well for long and that making Ciba free will just help it win more market share once for all.

The same model was applied again on the deal with Top100.cn, one of the largest online music libraries in China. Guo represented Google to talk the Big Four record companies to provide free online distribution of their songs. The labels can share the money from the advertising Google places on Top100.cn.

It’s hard to imagine in any other multinationals that Alan Guo, even as one of the persons behind Google China’s moves, could help create two major products within merely two years. That’s just the most valuable thing Google brings to China, a belief that everyone, from founder to each engineer, can initiate something different and make it happen with their efforts. Google Kingsoft Ciba and Music Search are not likely to be cash cows in near or middle term. But they point to more possibilities.

“If fighting for market share is the mission for a global company, then it’s on a dead direction. It needs to ignite people or to tell others how to make an egg stand on the table.” Guo says to us. “And I always believe that when you fight with dignity, you’ll have a dignified rival, and vice versa. When your rivals think they can learn something from you, probably they won’t rush to smash you.”

[Photos by Keso with some rights reserved.]

>> More posts

Advertisement

This site unofficially covers Google™ and more with some rights reserved. Join our forum!